Literacy was widespread in Muslim West Africa and, unlike the norm in Europe at the time, education was available across class and gender. Visiting Timbo (Guinea) in the early 1800s, French slave dealer, Theophilus Conneu, observed “many elderly females...soon in the morning and late at evening, reading the Koran.” Girls usually made up 20% of students in Qur’anic schools. Lamine Kebe, a Qur’anic teacher enslaved in the United States noted several girls among the students at his school in Futa Jallon (Guinea). He praised his aunt as “much more learned than himself and eminent for her superior acquirements and for her skills in teaching” and spoke of other “women who have been devoted teachers for life, and have rivaled some of the most celebrated of the other sex in success and reputation for talent and extraordinary acquisitions."

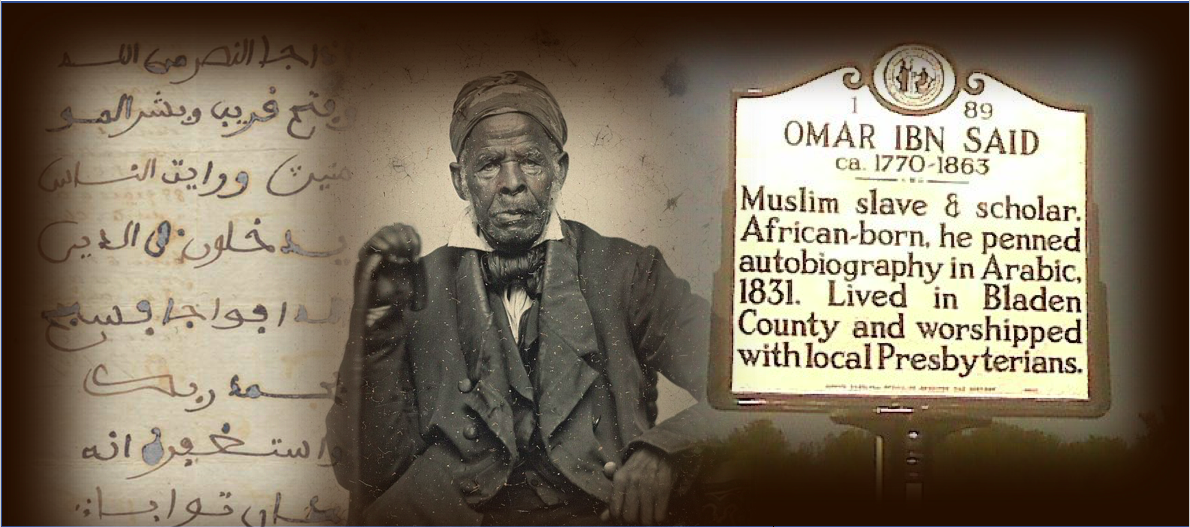

The autobiography of Omar ibn Sayid is just one example of early American literature filled with Qur'anic verses and written in Arabic by early Muslims in the country.

The autobiography of Omar ibn Sayid is just one example of early American literature filled with Qur'anic verses and written in Arabic by early Muslims in the country.

Literacy and Early American Literature by Muslims in the Colonies

Information from Sylviane Diouf's Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas.

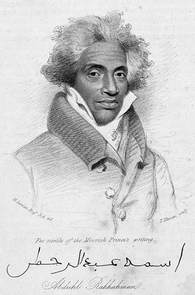

Ayuba Suleiman Diallo, Ibrahim Abd al-Rahman and Omar ibn Sayid are just a few of the Muslims who lived in early America. Learn about their stories below.

African Muslims first arrived in America in the 1500s. Historians estimate that 10- 30% of all Africans enslaved in the colonies were Muslim. To learn more about this history, visit the National Museum of African American History & Culture's page on African Muslims in America here.

Early Muslims in America

As a father in quest of freedom for his children to return with him back to Africa, Abdul Rahman embarked on a journey through Cincinnati, Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York City, Boston, Worcester, Salem, New Bedford, Massachusetts, Providence, Rhode Island and New haven and Hartford, Connecticut. He met with President John Quincy Adams, Secretary of State Henry Clay, and Francis Scott Key (then a member of the American Colonization Society’s board of managers). The President documented his meeting with Ibrahim, “otherwise called Prince, who has been forty years a slave in this country” in a journal entry on May 15, 1821. Along the way, “The Prince” captivated the country and raised public awareness of Islam. Newspaper articles not only shared his story, but sought to elucidate the public on key tenets of Islam.

The Autobiography of Abdul Rahman

I was born in the city of Tombuctoo. My Father had been living in Tombuctoo, but removed to be King in Teembo, in Foota Jallo. his name was Almam Abrahim. I was five years old when my father carried me from Tombuctoo. I lived in Teembo, mostly, until I was twenty one and followed the horesen. I was made Captain when I wasn twenty-one – after they put me to that , and found that I have a vergy good head, at twenty-four they made me Colonel. At the age of twenty six, they sent me to fight the Hebohs, because they destroyed the vessels taht came to the coast, and prevented our trade. When we fought, I defeated them. But they wen tback one hundred miles into the country, and hid themselves in the mountain. We coud not see them, and didn not expect there was any enemy. When we got there we, dismounted and led our hourses, until we were half way up the mountain. Theyn they fired upon us. We saw the smoke, we heard the guns, wes saw the people drop down. I told every one to run until we reached the top of the hill, then to wait for each other until all came there, and we would fight them. After I had arrived as the summit, i could see no one excpet my guard. they followed us, and we ran and fought. I saw this would not do. i told every one to run who wished to do so. Every one who wished to run , fled. I said I will not run for a Kufr. I got down from my horse and sat down. ………They sold me directly, with fity others, to an English ship. They took me to the Islamd of Dominica. After that I was taken to New Orleans. they the took me to Natchez and Colonel Foster brought me. I hae lived with Colonel Foster 40 years. thirty years I laboured hard. the last ten years I have been indulged a good deal. I have left five children behind and eight grand children. I feel sad, to think of leaving my children behind me. I desire to go back to my own country again; but when I think of my childre, it hurts my feelings. If I go to my own country, I cannot fell happy, if my children are left. I hope by God’s assistance, to recover them.

Omar ibn Sayid was captured in Senegal and taken into slavery in South Carolina before fleeing to Fayetteville, North Carolina. Like Ayuba Suleyman Diallo, he reportedly scrawled Arabic across the walls of his jail cell. In 1831, he penned a fifteen page autobiography that begins with the bismillah, “In the name of Allah, the merciful, the compassionate.” Before describing his life’s story, he quotes a surah or chapter from Qur’an, al-Mulk. Translated as “The Sovereignty” or “The Ownership,” this selection proclaiming God the creator of all things can be seen as an implicit challenge to earthly slavery. Omar ibn Sayyid’s legacy lives on in the Masjid Omar ibn Sayyid, a Fayetteville mosque still in operation today.

While many white colonists were either oblivious to the religious practice of their slaves or aggressively attempted to convert them to Christianity, the narratives of Ayuba Suleyman Diallo and Bilali Muhammad portray Muslims practicing their faith publicly and with permission from the white slave owners. On a Maryland plantation in the 1730s, Ayuba Suleyman Diallo prayed secretly as he tended cattle. Captured and thrown in jail after fleeing the plantation, he became notorious for writing Arabic on the cell walls. Hearing of his skill, his owner brought him back to the plantation, lightened his workload, and gave him a place to pray.

A devout Muslim captured from Guinea and shipped to Sapelo Island off the coast of Georgia in the early 19th century, Bilali Mohammed (also known as Bu Allah, Ben Ali, and Belali Mohamet), served as sole manager of a large island property home to 400-500 slaves. Bilali’s master, Thomas Spalding, permitted the Muslims to practice their religion openly, allowing Bilali to construct a small mosque on the plantation - possibly the first muslim prayer house in North America. During the War of 1812, Spalding and his family left the plantation, leaving Bilali in charge with eighty muskets to distribute among the slaves. Warned that Bilali and eighty other slaves were armed, the British did not invade his island. Bilali also saved his community during a major hurricane on September 14th, 1824, directing slaves into cotton and sugar houses made of the African material, tabby.

"Yarrow owns a House & lotts and is known by most of the Inhabitants of Georgetown… he professes to be a mahometan [Muslim], and is often seen & heard in the Streets singing Praises to God." Charles Peale 18